Mechanistic Model for Decision Making

From Deliberative Democracy Institiute Wiki

(Redirected from The cognitive elements of decision making)

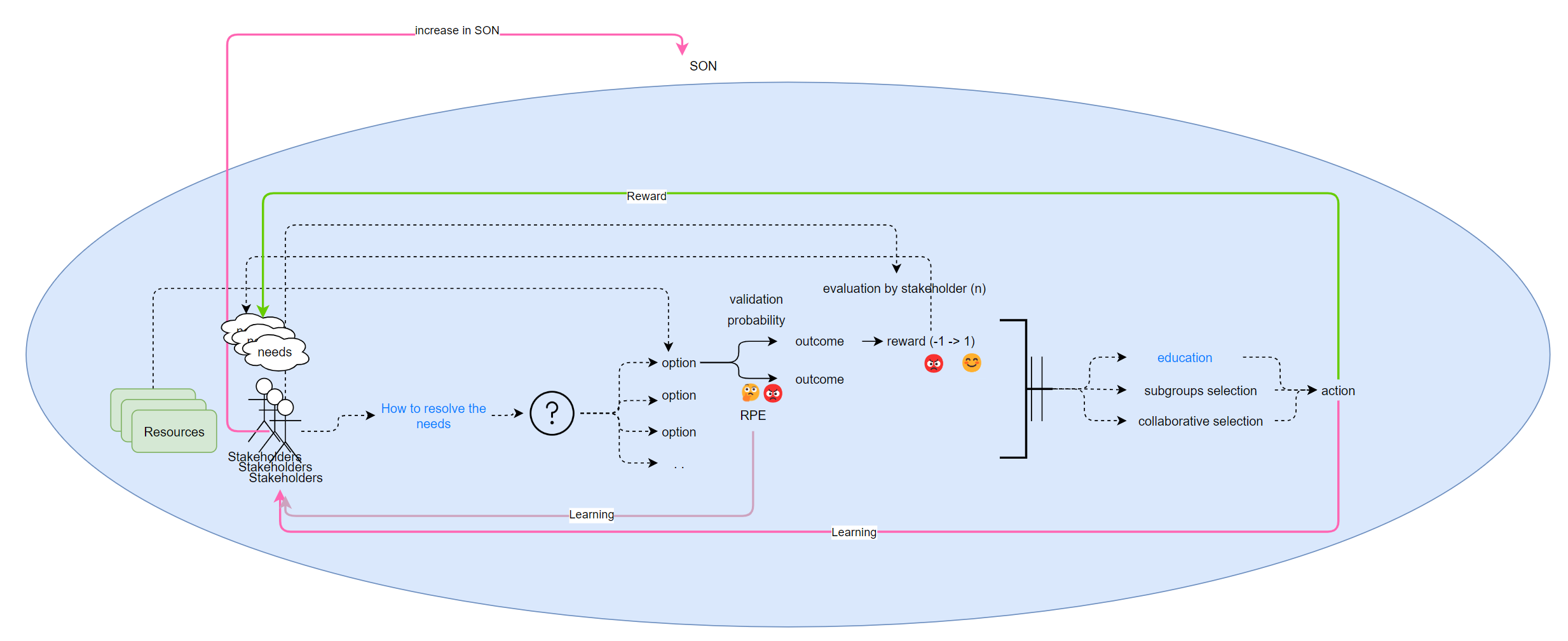

Decision-Making: A Cognitive Approach

This theory introduces a mechanistic model that delineates the intricate cognitive processes involved in decision-making. Drawing from psychological and epistemological perspectives, the proposed model elucidates the interplay of various mental elements during the decision-making process. The components include the identification of needs, consideration of stakeholders, formulation of questions, generation of options, and the subsequent evaluation, selection, and implementation of decisions. Furthermore, the model incorporates the concept of a Mental Objects Network (MON) to elucidate the role of interconnected theories in shaping decision outcomes. The paper underscores the importance of resource analysis, value attribution to outcomes, and the nuanced consideration of probability in optimizing decision outcomes. Additionally, it explores the influence of familiarity and external factors on decision selection, emphasizing the role of learning in the development of a corroborated System of Neural (SON) essential for better predictions.

Decision-making is a multifaceted cognitive process involving intricate mental elements that synergistically contribute to the formulation of choices. This paper presents a comprehensive mechanistic model that elucidates the underlying cognitive mechanisms governing decision-making.

Elements

Need Identification

The decision-making process commences with the identification of needs, representing a biological signaling process within the brain, indicating a lack of essential resources. These resources can manifest in both physical and emotional domains, aligning with established psychological paradigms such as Maslow's hierarchy of needs.

Stakeholders

Stakeholders, encompassing both organizational members and external entities, play a pivotal role in decision-making by virtue of being potential recipients of the consequences stemming from organizational actions. A thorough understanding of stakeholders and their interests informs the decision-making process.

Question Formulation

Questions serve as cognitive tools facilitating information gathering and initiation of the decision-making process. The formulation of relevant queries directs the subsequent exploration of potential solutions to address identified needs.

Options

The decision space is delineated by the generation of options, each representing a potential avenue for fulfilling identified needs. These options, when meticulously analyzed, form the basis for subsequent evaluation and selection.

Mental Objects Network

The proposed model introduces the concept of a Mental Objects Network (MON) to elucidate the interconnected nature of theories within the brain. The MON, comprised of mental objects representing our understanding of the world, plays a crucial role in shaping decision outcomes.

For further explanation, see epistemology.

Outcomes Analysis

Every option culminates in specific outcomes, each carrying a distinct value ranging from rewarding to taxing and even endangering. The theory emphasizes the need for a nuanced evaluation of these outcomes to inform decision-making.

Resources

Every option consumes resources, necessitating a consideration of available resources when evaluating options. Resource analysis is integral to the decision-making process, as each option consumes resources. A judicious consideration of available resources is essential in assessing the feasibility and sustainability of potential decisions.

Value

Outcomes have varying values, ranging from rewarding to neutral or taxing, affecting our physical and emotional resources. Each stakeholder has different resources and values, which affect the value of each option.

Validation

When assessing options, participants can gauge their validity by aligning them with their Mental Object Network (MON) as well as the Social Object Network (SON) they uphold. They should scrutinize if the options contradict other established observations. For instance, if a participant claims that accessing the beach via bus line 29 is feasible, another participant might counter by verifying official information, revealing the absence of such a bus line. This validation process mirrors the Popperian falsification method[1], aiming to refine the accuracy of assertions.

Probability of Success

Participants should evaluate the probability of potential outcomes occurring. While a particular outcome may seem plausible, its likelihood of occurrence might not meet the desired threshold. The probability of success is a crucial factor in the decision-making process. Each option, being a sequence of events, carries varying probabilities of successful realization. Accurately estimating the probability of the desired outcome should significantly influence the chosen course of action.

Resources

For every action, which is based on the option we selected, there is a tax on our resources. Before we evaluate options, we should also consider how much resources do we have, and if we have the specific resources needed for the option.

Evaluation

When faced with a list of options, stakeholders may evaluate the overall outcome benefits, necessary resources, and likelihood of success of options. Each stakeholder will assess option's return on investment (ROI) based on their individual needs and resources, which may differ significantly from those of other stakeholders. These evaluations will often be expressed through emotions. A positive evaluation will typically manifest as joy or agreement, while a negative evaluation may result in resentment or even anger. In cases where the outcomes of the decision appear likely to adversely impact a stakeholder, they may react with anger and fear.

Selection

Optimal decision-making involves comparing the total value of each option and choose the one with the highest value. External factors may influence decision-making, such as familiarity with an option, even if better alternatives exist.

Selection involves the comparison of available options and selecting the one that provides the best value. However, for various reasons that we will discuss later, we may not evaluate all options or choose the one we are more familiar with, even if there are better options available. The process of selecting an option is also known as making a decision.

Action

To improve decision-making, every selection should be followed by actions designed during the selection phase. This will help the group learn from experience and improve their SON.

Learning

Learning is a continuous process involving hypothesis formulation and testing. Decision-making and practical experiences contribute to developing a corroborated System of Neural (SON), forming the basis for accurate predictions. Learning occurs through personal experiences, testing theories, and considering insights from others.

See also

Next: Neuropsychology elements in decision making

References

- ↑ Popper, K. (2002). The Logic of Scientific Discovery (Routledge Classics). Routledge.